Types and Multiple Dispatch in Julia

Julia is primarily a functional programming language. Instead of building classes and defining methods for these classes – as you would in an object-oriented programming language – you typically focus on writing functions that manipulate data.

This is not to say that Julia doesn’t make use of object-oriented concepts at all. Each value in Julia is assigned a type (similar to a class in other languages), which limits the space of possible values it can store. Having a (rough) understanding of Julia’s type system is useful for developing efficient code and can be leveraged for structuring your own research projects.

This post is a tutorial on how to define your own types and methods. As a running example, I use user-defined types and methods from my applied econometrics module MyMethods.jl. You can find the most recent version of the package on github.com/thomaswiemann/MyMethods.jl.

There are three topics that seem particularly useful for taking advantage of Julia’s type system. These are:

- Composite types

- Multiple dispatch

- Abstract types and type hierarchy

Let’s discuss each in turn!

Composite types

There are two types of concrete types – i.e., types that store data – in Julia: primitive types and composite types. While primitive types directly carry bits (e.g., Float64 is 64-bits wide), composite types carry a set of named fields. These named fields can be assigned primitive types or other composite types.

Collecting values within composite types allows for easier manipulation of data and often improves structure, which can make them a convenient tool for larger research projects.

Suppose we are interested in implementing a simple least squares estimator in Julia. At first, we may be tempted to simply define a function, say myLS, that takes two arrays and returns the coefficient:

function myLS(y::Array{Float64}, X::Array{Float64})

# Calculate and return the LS coefficient

return (X' * X) \ (X' * y)

end #MYLS

Most projects don’t stop at there, however. We might want to calculate the coefficient’s standard errors, or use it for prediction. These could be simply implemented in another Julia function:

function predict(β::Array{Float64}, X::Array{Float64})

# Calculate and return the predictions

return X * β

end #PREDICT

function inference(β::Array{Float64}, y::Array{Float64}, X::Array{Float64})

# Obtain data parameters

N = length(y); K = size(X, 2)

# Calculate the covariance under homoskedasticity

u = y - predict(β, X) # residuals

XX_inv = inv(X' * X)

covar = sum(u.^2) * XX_inv

covar = covar .* (1 / (N - K)) # dof adjustment

# Get standard errors, t-statistics, and p-values

se = sqrt.(covar[diagind(covar)])

t_stat = β ./ se

p_val = 2 * cdf.(Normal(), -abs.(t_stat))

# Organize and return output

output = (β = β, se = se, t = t_stat, p = p_val)

return output

end #INFERENCE

Notice that each time we want to calculate predictions, we need to pass both the regression coefficient β as well as an array of features X. When calculating standard errors, we’d also need to pass the outcomes y. This can quickly become bothersome and increase clutter in your code.

That’s where the named fields of a composite type come in handy! Instead of defining the least squares implementation using the function keyword, we can define our own Julia type using struct:

struct myLS

β::Array{Float64} # coefficient

y::Array{Float64} # response

X::Array{Float64} # features

# Define constructor function

function myLS(y::Array{Float64}, X::Array{Float64})

# Calculate LS

β = (X' * X) \ (X' * y)

# Organize and return output

new(β, y, X)

end #MYLS

end #MYLS

There are two key parts to these bits of code. The first few lines define the named fields of the newly defined type. These are β, y, and X. In the second part, we define the (inner) constructor function. Notice that it is in essence similar to how we defined the least squares function at the beginning of this section. The key difference is that instead of using return to pass the results, a new object is constructed using new().

So how can the prediction and inference functions take advantage of the new type? Instead of passing multiple arguments, it is now possible to define the functions using only an object of type myLS as input. For example:

function predict(fit::myLS, data = nothing)

# Check for new data, then calculate and return predictions

isnothing(data) ? fitted = fit.X * fit.β : fitted = data * fit.β

return(fitted)

end #PREDICT.MYLS

function inference(fit::myLS)

# Obtain data parameters

N = length(fit.y); K = size(fit.X, 2)

# Calculate the covariance under homoskedasticity

u = y - predict(fit.β, fit.X) # residuals

XX_inv = inv(fit.X' * fit.X)

covar = sum(u.^2) * XX_inv

covar = covar .* (1 / (N - K)) # dof adjustment

# Get standard errors, t-statistics, and p-values

se = sqrt.(covar[diagind(covar)])

t_stat = fit.β ./ se

p_val = 2 * cdf.(Normal(), -abs.(t_stat))

# Organize and return output

output = (β = fit.β, se = se, t = t_stat, p = p_val)

return output

end #INFERENCE.MYLS

If you’re not yet incredibly excited – don’t fret. While collecting related values through composite types is often handy, the real payoff from leveraging Julia’s type system is through it’s multiple dispatch process.

Multiple dispatch

Whenever a command is run, a dispatch process is launched in which the function to be executed is determined. In Julia, this process – called multiple dispatch – determines the function using the types of the function arguments. This implies that multiple functions can carry the same name as long as their argument types differ.

If you have already been coding in Julia, you likely made use of multiple dispatch many times. Consider, for example, the following bits of code:

"hello, " * "world!"

julia> "hello, world!"

21 * 2

julia> 42

The operator * thus maps to different functions, which are evidently different depending on whether its arguments are of type String or of type Int64. And this thankfully so. Coding Julia would be substantially more cumbersome if functions would only take arguments of a predefined type (just think about all the subscripts we’d need for basic arithmetic operations alone!).

To showcase how multiple dispatch can be leveraged to streamline your research projects, consider that in addition to the myLS type of the previous section, we also wanted to implement a two-stage least squares estimator and call its type, say, myTSLS. Using the struct keyword as before, this can be done as follows:

struct myTSLS

β::Array{Float64} # coefficient

y::Array{Float64} # response

Z::Array{Float64} # combined first stage variables

X::Array{Float64} # combined second stage variables

FS::Array{Float64} # first stage coefficients

# Define constructor function

function myTSLS(y::Array{Float64}, D::Array{Float64},

instrument::Array{Float64}, control = nothing)

# Add constant if no control is passed

if isnothing(control) control = ones(length(y)) end

# Define data matrices

Z = hcat(control, instrument) # combined first stage variables

X = hcat(D, control) # combined second stage variables

# Calculate matrix products

ZZ = Z' * Z

DZ = X' * Z

Zy = Z' * y

FS = inv(ZZ) * DZ'

# Calculate TSLS coefficient

β = (DZ * FS)' \ (FS' * Zy)

# Return output

new(β, y, Z, X, FS)

end #MYTSLS

end #MYTSLS

As with the least squares implementation, a set of functions that use the two-stage least squares output, e.g., for prediction and inference, would be helpful. Instead of renaming the functions defined for the myLS object defined earlier, or giving the new functions for the myTSLS object obscure names (such as predict_myTSLS() and inference_myTSLS() [uff]), we can simple create functions under the same name but with a different argument type. For example:

function predict(fit::myTSLS, data = nothing)

# Check for new data, then calculate and return predictions

isnothing(data) ? fitted = fit.X * fit.β : fitted = data * fit.β

return(fitted)

end #PREDICT.MYTSLS

function inference(fit::myTSLS)

# Obtain data parameters

N = length(fit.y)

Kz = size(fit.Z, 2)

Kx = size(fit.X, 2)

# Calculate the covariance under homoskedasticity

u = fit.y - predict(fit) # residuals

PZ = fit.Z * fit.FS

PZZPinv = inv(PZ' * PZ)

covar = sum(u.^2) .* PZZPinv ./ (N - Kz)

# Get standard errors, t-statistics, and p-values

se = sqrt.(covar[diagind(covar)])

t_stat = fit.β ./ se

p_val = 2 * cdf.(Normal(), -abs.(t_stat))

# Organize and return output

output = (β = fit.β, se = se, t = t_stat, p = p_val)

return output

end #INFERENCE.MYTSLS

Instead of cluttering our code with subscripts, Julia’s multiple dispatch will determine the correct prediction or inference function depending on whether we pass an object of type myLS or myTSLS. This should come in pretty handy, especially as we add additional types of estimators, for which we also want to define prediction and inference functions.

If you’ve gone through the code carefully, you may have noticed that the prediction functions are identical except for the type of input argument. There are many reasons against copying code in this manner, including worse readability. The next section discusses how type hierarchies can be used for sharing methods across objects of different types.

Abstract types and type hierarchy

In addition to concrete types, Julia also has abstract types. Some abstract types defined in Base Julia are Real or AbstractFloat (duh!). Abstract types do not carry any data and cannot be explicitly constructed. Instead, their use lies in grouping objects so that functions can be shared across their sub-types.

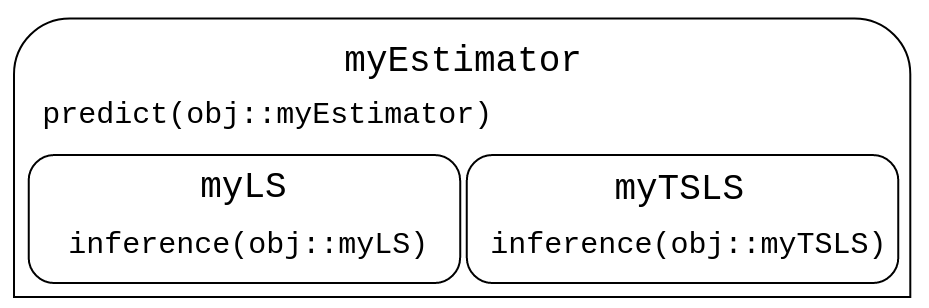

In the previous section, we encountered a scenario where predict() is the same for arguments of type myLS and myTSLS, but where inference() differs. We thus want some – but not all – of the functions to be shared across types. It might therefore be useful to group the two existing types under the umbrella of an abstract type called, say, myEstimator. The below figure illustrates the type hierarchy and how the prediction and inference functions should be shared.

To define the myEstimator abstract type, we use the keywords abstract type:

abstract type myEstimator end

The <: operator is used to define a subtype relationship. Instead of defining the myLS and myTSLS objects as before, we need to add <: myEstimator next to the type names as follows:

struct myLS <: myEstimator

# [insert code from earlier here]

end #MYLS

struct myTSLS <: myEstimator

# [insert code from earlier here]

end #MYTSLS

(Of course, you should include the code from the earlier definitions of the objects here. I don’t here, but purely for reasons of conciseness.)

Instead of defining a prediction function for both myLS and myTSLS, it then suffices to only define one for arguments of type myEstimator:

function predict(fit::myEstimator, data = nothing)

# Calculate and return predictions

isnothing(data) ? fitted = fit.X * fit.β : fitted = data * fit.β

return(fitted)

end #PREDICT.MYESTIMATOR

The inference functions defined in the previous subsections do not need to be amended to work with the newly defined type hierarchy.

This concludes my introduction to types and multiple dispatch in Julia.